©️ By Sophie Lewis | The Grooming Files

Long before grooming gang cases reached courtrooms, another decision had already been made.

Not by offenders, but by the institutions meant to protect children.

The decision was this..

that the girls being abused were the risk.

Once that framing took hold, everything else followed.

How Language Was Used to Disarm Safeguarding

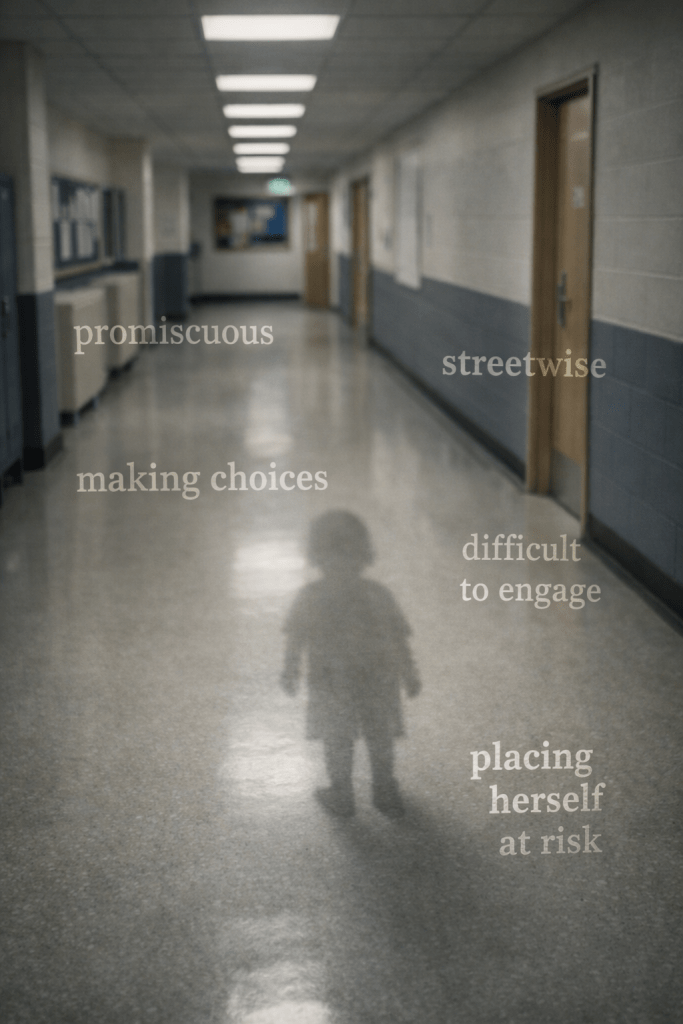

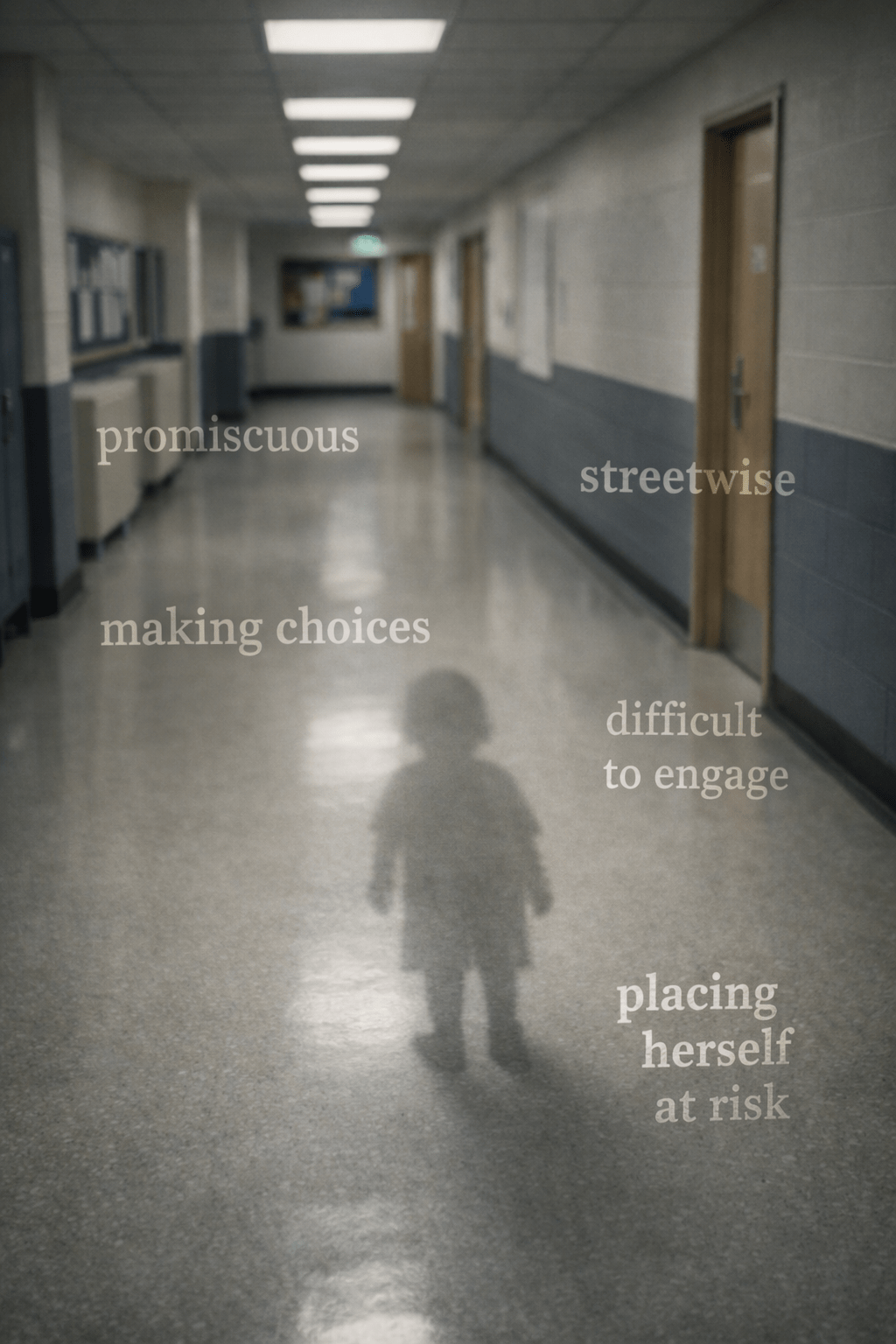

Across grooming gang cases, the same words appear again and again in records, assessments, and professional notes.

Girls were described as:

- “promiscuous”

- “streetwise”

- “sexually active”

- “hard to engage”

- “making choices”

- “placing themselves at risk”

These weren’t neutral descriptions.

They were protective language, not for the child, but for the system.

Because once a child is framed as choosing risk, the obligation to intervene weakens.

From Victim to Liability

The shift was subtle but devastating.

Instead of asking:

Why are adult men targeting this child?

The question became:

Why does this child keep putting herself in danger?

That reframing did several things at once:

- It stripped the child of credibility

- It lowered the urgency of intervention

- It shifted responsibility away from perpetrators

- It justified professional inaction

Abuse didn’t disappear.

It was administratively neutralised.

Oxford: When “Difficult” Meant “Not Our Problem”

The 2015 Serious Case Review into Oxfordshire explicitly documented this reframing in action.

The review found that professionals “saw the girls as the source not the victims of their extreme behaviour”.

Girls who were being systematically abused were described in records as:

- “very difficult”

- “making bad choices”

- displaying “extreme behaviour”

The review stated clearly:

“That the girls had lost the ability to consent or make their own decisions due to grooming was not realised.”

Instead, frequent missing episodes were “put in the context of them being extremely difficult children” rather than evidence of ongoing exploitation.

The abuse continued for years while professionals recorded concerns about the girls’ behaviour, not the men abusing them.

“Consenting” — The Word That Should Never Have Been Used

Perhaps the most corrosive reframing of all was the suggestion of consent.

Girls as young as 13, 14, 15 were described implicitly or explicitly as “consenting”, “sexually aware”, or “choosing relationships”.

This language ignored a basic truth:

Children cannot consent to their own exploitation.

But by leaning on sexualised stereotypes, particularly of working-class girls in care institutions found a way to downgrade abuse into behaviour management.

Once that happens, safeguarding stops being about protection and starts being about control.

Why Certain Girls Were Easier to Ignore

Not all victims were treated the same.

Those most likely to be dismissed shared common characteristics:

- in care or on the edge of care

- from deprived backgrounds

- already labelled “troubled”

- with prior involvement from police or youth services

Their histories were used against them.

Past trauma became evidence of unreliability.

Distress became proof of instability.

Survival behaviour became “choice”.

The system didn’t just fail these girls.

It judged them.

Professionals Didn’t Need to Be Cruel — Just Comfortable

This wasn’t about individual malice.

Most of the professionals involved weren’t predators or villains.

They were people operating inside a culture that rewarded risk avoidance, not child protection.

A culture where:

- escalating concerns meant paperwork and scrutiny

- challenging colleagues meant conflict

- naming abuse meant institutional consequences

So the easier path was taken.

Language softened.

Risk was reframed.

Responsibility was diffused.

And children paid the price.

This Pattern Isn’t Unique to Grooming Gangs

What makes this especially dangerous is that it isn’t confined to grooming gang cases.

The same reframing appears in:

- school abuse cases

- care home scandals

- online exploitation

- peer-on-peer abuse responses

Different context.

Same mechanism.

When systems struggle to act, they often solve the discomfort by redefining the victim.

Why This Still Hasn’t Been Properly Confronted

Even now, discussions about grooming gangs often focus on:

- policing failures

- community tensions

- prosecution rates

What’s talked about far less is how institutional language enabled abuse to continue.

Because confronting that means admitting something uncomfortable:

That harm wasn’t just overlooked.

It was managed.

The Question We Still Avoid

The most dangerous question isn’t “why didn’t we know?”

It’s this:

Why was it easier to believe these girls were the problem than to act against the adults abusing them?

Until institutions answer that honestly, safeguarding reforms will keep failing.

And children will keep learning the same lesson:

That telling the truth doesn’t always mean being protected.

Sophie Lewis | NUJ-Accredited Investigative Journalist

The Grooming Files

Next in this series: “What Happened to the Girls After the Trials Ended?”

Sources:

- Serious Case Review into Child Sexual Exploitation in Oxfordshire (2015)

- Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham 1997-2013 (Jay Report, 2014)

- National Audit on Group-Based Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (Casey Report, 2025)

Leave a comment