©️ By Sophie Lewis | The Grooming Files

For years, the dominant narrative around grooming gangs has been one of invisibility.

That the abuse was “hidden”.

That nobody knew.

That the signs were missed.

But serious case reviews, court transcripts, and victim testimony tell a very different story.

The abuse wasn’t invisible.

It was reported.

It was documented.

And again and again, it was deprioritised.

What failed wasn’t sight.

It was will.

The Myth of the Missed Signs

In town after town, victims of organised child sexual exploitation told professionals what was happening to them.

They told social workers.

They told teachers.

They told police officers.

They told youth workers.

They described older men picking them up in cars.

Being taken to flats and takeaways.

Being given alcohol, drugs, money, “attention”.

Being raped by multiple men.

These disclosures didn’t vanish into thin air.

They were recorded.

What followed wasn’t intervention — it was reinterpretation.

When the System Rewrites the Risk

Instead of responding to abuse, agencies reframed it.

Girls were described as:

- “promiscuous”

- “streetwise”

- “making lifestyle choices”

- “difficult to engage”

- “placing themselves at risk”

The risk was subtly relocated — away from adult perpetrators and onto the child herself.

Once that shift happens, everything else follows.

Safeguarding thresholds rise.

Urgency falls.

Responsibility dissolves.

The child becomes “the problem”.

The abuse becomes background noise.

Rotherham: 1,400 Victims, “Undesirables” and “Lifestyle Choices”

The 2014 Jay Report into Rotherham found that at least 1,400 children had been sexually exploited between 1997 and 2013. Children as young as 11 were raped by multiple perpetrators, trafficked, beaten and intimidated.

Police officers called the victims “tarts” and “undesirables” — children they knew were being sexually exploited by adults.

The abuse wasn’t hidden. It was reported. Victims were known to multiple agencies. Many were in care, repeatedly going missing, flagged as vulnerable.

The Jay Report found that “the police had shown a lack of respect for the victims in the early 2000s, deeming them ‘undesirables’ unworthy of police protection.”

When professionals see children this way, intervention becomes optional.

Oxford: “Very Difficult Girls Making Bad Choices”

The 2015 Serious Case Review into child sexual exploitation in Oxfordshire examined cases where girls as young as 11 were subjected to what one victim described as a “living hell”.

The official review found:

“They were seen as very difficult girls making bad choices. That the girls had lost the ability to consent or make their own decisions due to grooming was not realised.”

“The language used by professionals was one which saw the girls as the source not the victims of their extreme behaviour.”

The abuse continued for years. Seven men were convicted. Five received life sentences.

The victims had been screaming for help the entire time.

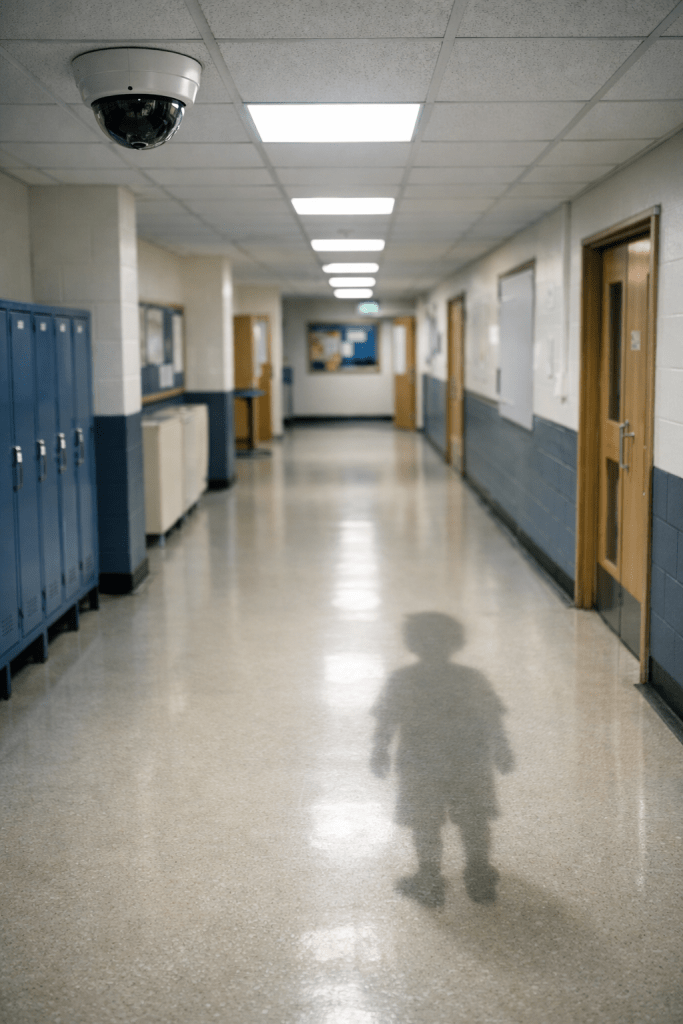

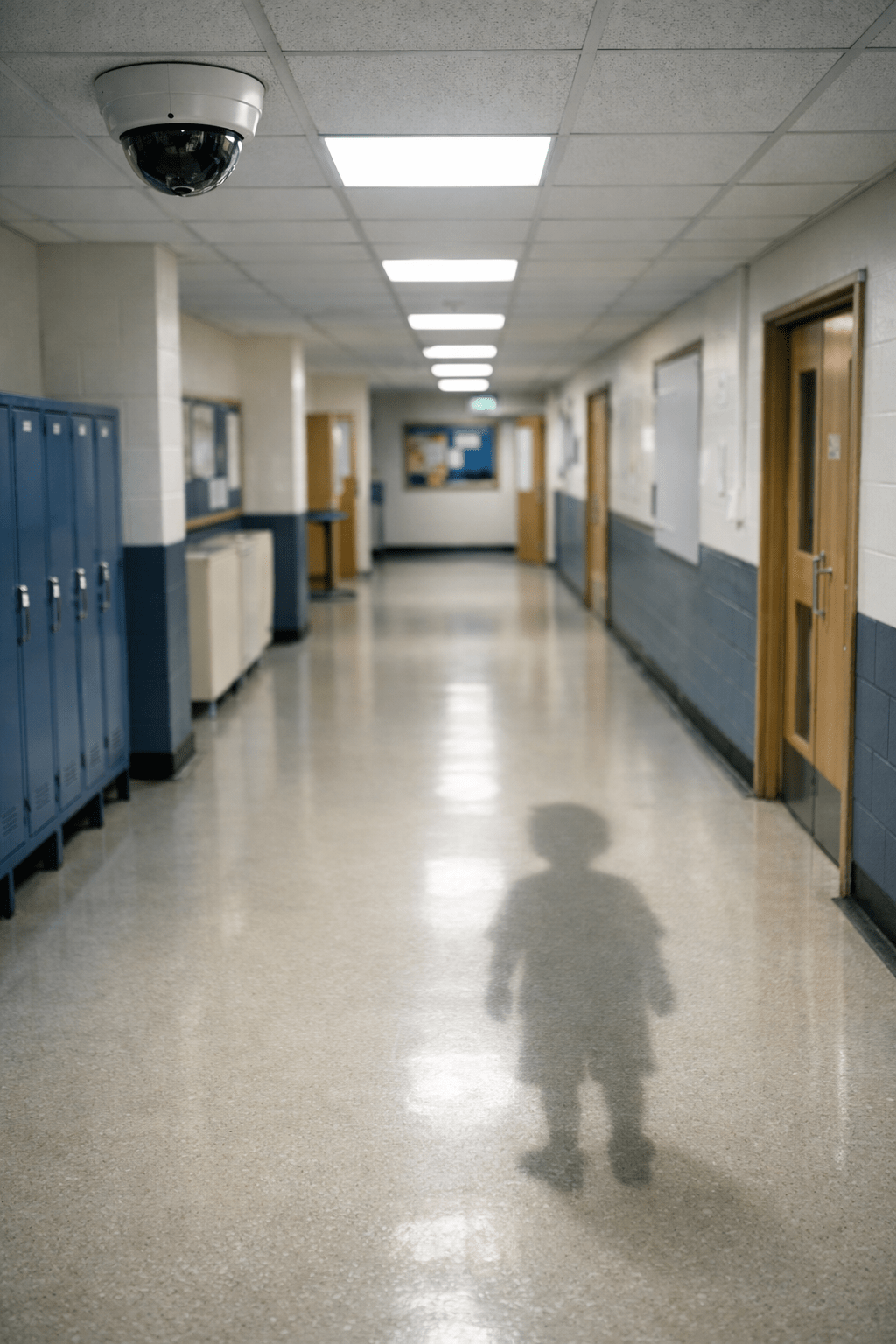

Known to Services, Left There Anyway

One of the most consistent findings across grooming gang cases is this:

Victims were already known to multiple agencies.

Many were:

- in care or on the edge of care

- flagged for missing episodes

- known to youth offending teams

- identified as vulnerable

They weren’t invisible children.

They were highly visible — just not prioritised.

Professionals knew these children were being harmed.

What they didn’t do was act decisively enough to stop it.

Fear, Paralysis, and Reputation Management

So why didn’t authorities intervene?

The reasons given are depressingly consistent:

- fear of “getting it wrong”

- concern about community tensions

- uncertainty over evidential thresholds

- belief that victims were unreliable

- reluctance to escalate without a “clear offence”

In practice, this meant waiting.

Waiting for stronger evidence.

Waiting for the “right” moment.

Waiting until the harm was undeniable.

By the time it was undeniable, the damage was already done.

This Wasn’t a Blind Spot — It Was a Choice

Calling this a “failure to spot abuse” lets institutions off the hook.

The reality is harsher.

Abuse was spotted — repeatedly.

It just wasn’t acted on with the seriousness it demanded.

That isn’t blindness.

It’s a systemic decision to tolerate risk until it becomes unavoidable.

Why This Still Matters

Grooming gang cases are often framed as a problem of the past.

They’re not.

The same mechanisms that allowed organised abuse to continue unchecked still exist:

- risk reframing

- victim credibility erosion

- institutional fear culture

- escalation paralysis

Different setting.

Same failure.

Schools.

Care homes.

Online spaces.

Peer groups.

When institutions prioritise reputation, process, or comfort over child protection, abuse doesn’t need to hide.

It just needs to wait.

What Comes Next

If we keep telling ourselves that grooming gangs “went unnoticed”, we miss the real lesson.

The danger isn’t that we don’t see abuse.

It’s that we see it — and convince ourselves it’s someone else’s problem.

Until that changes, new safeguarding bodies, new reviews, and new promises won’t protect children.

They’ll just explain, again, why nobody acted in time.

Sophie Lewis | NUJ-Accredited Investigative Journalist

The Grooming Files

Next in this series: “When the System Decided the Girls Were the Problem”

Sources:

- Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham 1997-2013 (Jay Report, 2014)

- Serious Case Review into Child Sexual Exploitation in Oxfordshire (2015)

- Hampshire Police press releases

- Crown Prosecution Service official statements

Leave a comment